To judge from the credits alone - brief glimpses of shades-wearing men having seedy conversations; shots of wads of lira; guns - RC is either a shitty cheesy crime drama set in the 70s in the vein of the Professionals, or a cool Goodfellas-style fast-paced anthropological study of Italian crime in Italy. Even the promo photo looks shit. Happily, this story of the real-life Banda della Magliana is neither; fortuitously, it is the greatest TV programme maybe ever.

It is a bildungsroman of a gang, centring on its leader, small-time hood Lebanese, who lives in a small caravan by the Tiber. Inevitably, he forges alliances with local hoods and runs risks with dogged determination as they come up against better-connected foes and the sinister Camorra. So far so Scarface. But we who know little about the Banda in advance of its screening are never given the sense that their rise to power will be inevitable in the same sense as a Hollywood gangster epic. Limited by their running time, the big screen bildungsroman defaults to vignettes, presenting the trajectory of character in a single unvarying gradient, always seeming like an abridged biography retold by an omniscient narrator. Romanzo Criminale's format, whilst conforming to type with its 12 intriguing introductions and 12 cliff-hanger endings, allows many twists and set-backs and seems much closer to a geniune thriller than a morality tale, which is effectively what Scarface, Goodfellas, et al. are. In fact, the gang's transition from small-time hoodlumry to the big stage establishes once and for all supremacy of the novel and the TV series over story, film and stage in matters of exposition.

Most interesting is the fact that RC is set during Italy's anno di piombi. This is the most triumphant detail in the series. The historical gravitas of Italy's torrid recent past elevates Criminale way, way above run-of-the-mill crime dramas and makes HBO centrepieces like the Sopranos look like a dreary soap-opera and Life on Mars like the fantasy it is (people with no historical sense have compared it to both). The series begins like the flashbacks in Godfather Part 2 and hits another level when Aldo Moro is kidnapped by the Red Brigades. It is the crucially-important historical backdrop which makes the Italian state itself - in the form of the shady secret service, the identity of whose acolytes we see interspersed throughout the series, is only very slowly revealed - complicit in breaking the rule of law in exactly the same way as the Banda did. They are morally equivalent, these murdering thieves from the poor part of Rome and the security service, the writers tell us. The facts bear out the claim.

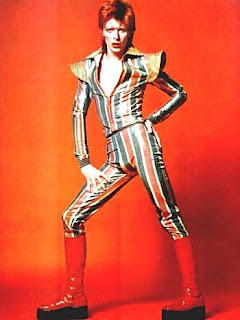

BP wasn’t alive to experience the 1970s in Italy, so we will refrain from posturing about its historical authenticity, but it looks and feels like a different, grubbier, less technologically sophisticated era and one familiar from archive footage. We know that the 1970s in Western Europe saw serious threats to the established order in the form of Communism, trade unionism, terrorism (Red, Black and anti-colonial) and, perhaps most of all, the Yom Kippur War and the resulting oil crisis of 1973. The piece of the pie seemed to get smaller across the West. A new, grubbier realism set in after the optimism of the 60s. It even saturated Hollywood. Watergate happened. Baader-Meinhof were running crazy across West Germany. The British army were shooting civilians in Ulster. Men were dressing up as women and pretending to be space aliens with 1950s’ licks. The US pulled out of ‘Nam, unable to defeat a determined army of peasants with AKs. Were the liberal values of the West falling apart? Was Communism going to take over?

The Years of Lead as presented in Criminale show the audience that Italy, far from being the land of fashion, pasta and football familiar to English-speaking contemporaries, was - is - an intensely political nation divided, like much of Europe, into three camps by its reaction to Anglo-capitalism. Firstly, the left, the Red Brigades and Anarchists, who kidnapped and murdered the Prime Minister of Italy, Aldo Moro in 1978 (we are given a glimpse of this through Inspector Scaiola's relationship with his Red sister); then the right, the fascists and Mussolini revivalists, whom we see when the fascist adventurer Nero (brilliantly played by an Iggy Pop lookalike) needs someone to launder his money; and finally, the centre, the dominant party of acquiescent capitalists after the fall of Mussolini, typified by Berlusconi. It is in the centre where the Banda (in spite of its links to NAR) and their nemesis Inspector Scaiola exist. The Banda believe in money, Scaiola in reason, together the two values uniting the centre faction: capital and law, the means of enforcing capital. By contrast, the secret service seem like out-of-control puppet masters, unsure which marionette to play with more. According to the producers, they played the Banda over Scaiola and the Right over the Left. But they don’t want more money and, as far as we can tell, they don’t want a second Duce.

The dichotomy between rifht and left resolved itself and the Years of Lead ended, but not before 85 people were blown up in Bologna. So, what of the era hinted at by the end of the first series of Romanzo? Governments calmed down, or got better at covering themselves up. The populace was tired of terrorism and pacified by the financial boom of the 1980s. Liberal markets triumphed across most of the world in 1991; Kojeve’s end of history thesis came to fruition. Francis Fukuyama updated it with an audacious piece of backwards clairvoyance. Markets opened up to freer trade. Governments trusted each other to be more predictable than in the 70s and real political choice between Red, Black and Centre was replaced with consumer choice. Companies, too, reacting to legislation to better secure national income, sought to make revenues more predictable, employing Black-Scholes and the personal computer to master the future and conquer risk (suggested further reading: Galbraith’s Affluent Society).

We live in a world a start-up Banda would have dreamed of – the approval and promotion of crass materialism, the ability to get-rich-quick and the chaos of globalisation as a smoke screen for their underworld activity. If the NAR or the CPI had got into power, they would have been toast.

More on the Banda:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Banda_della_Magliana