About a year ago I bought a house with my girlfriend - our first - and we decided to grow the garden from scratch. It was a new build, so the

jardin was a clay mess, a crenellated turbid 'scape which would have furnished Otto Dix with

enough material to fill in the blanks in his Alzheimered dotage.

This is what I did: I got rid of the detritus, the torn texile swatches of rubble-sacks, nails, breeze-blocks, bizarre twisted metal that looked as if it were from some autochthonous steampunk civilisation lost to history; I sowed out the stones and the rubble from the thinnest layer of soil-dust; I broke down the clay with my spade; I flattened out the craters from where the rubbish had been picked; I put down compost and sharp sand and fertiliser and grass seed; and - life came. Grass and earthworms and horrendous knotgrass and thistles and harlequin ladybirds ventured from the reclaimed wilderness. But it is my garden and I am happy.

I am Isak, forger in the wilderness, a rugged survivalist, a primitive ignorant of money and clock-time, but sympathetic to nature's time, the more fundamental time of organic life, regarding the changing seasons as my calendar and wrist-watch, completely attuned to the needs of the belly and the body, to man in his natural state, to the growth of the soil.

Yes, we at Burning Pyre also don't believe that soil grows, but what the fuck: Hamsun's book won him the Nobel Prize three years after its publication in 1917, back when the Prize was a Scandinavian gentlemen's club and before the word 'post-colonial' was coined.

By 1920, Hamsun had already written a swath of modernist texts, the most famous of which is

Hunger, a book widely read today and arguably the bridge between dark Russian psychologism of the 19th century and the urban alienation of the 20th century. Like one of those writers, Celine, was later to do, Hamsun toured the US. To judge from

Growth of the Soil, what he learned was hatred of money and love of the countryside.

So Hamsun wrote a novel about man in his totally natural, ahistorical state, what Spengler meant when he referred to the prehistoric skirmishes of the Cherusci or the Wolofs as a fight between ant colonies. History does not begin until there is a written chronicle; it falls away where there is no need for one. This is the ahistorical world of Isak.

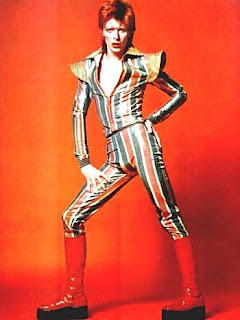

- Some soil, yesterday

Of course, this doesn't mean that the novel is without events. Like the earth, the story moves through its own seasons, beginning with a preface redolent of 'spring', in which Hamsun explains how Isak created a simple dwelling and began to live off the land. Through Isak's determination and his own labour, he builds instead of mud a house of wood, buys livestock and settles down with a female who wanders onto his land, a woman called Inger, afflicted with a hare lip, but a modest companion and a hard worker.

Together, Isak and Inger start a family and all is fine until Inger births a daughter with a cleft palate. In true

Aktion T4 style, she strangles it. In Hollywood, this would be the real opening of the story, the point at which the city-dwelling audience, torpid but unsated by an infinity of pleasures, ever-envious of what everyone else has, achieves the satisfaction it had been waiting for when it bites into the delicious apple-shaped schadenfreude of

trouble in rural paradise. In Hamsun, Inger's cruel act is the hard fact of human nature that people are driven by desperation to do terrible things.

The murder is a doorway to the real theme of the novel, one close to Hamsun's heart and one increasingly difficult to grasp in the ever-urbanising West of the 21st century. Inger is imprisoned and returns home after a lengthy spell in the city prison, miles and worlds away from the remote rural setting of her Isak and her sons, with her cleft lip corrected, a daughter and, most crucially, a new Weltanschauung. Gone is the demure inverted-

ingenue Inger, who displays the features of Hamsun's ahistorical tapestry of 'spring'; in her place is someone else, someone different - a self-conscious Inger, a world-weary, jaded Inger, a physically improved but morally degraded Inger, who feels herself above the work she had performed before she was incarcerated.It takes an act of gentle physical persuasion from Isak to set her back in her place with him. Inger withdraws and finds religion, but also re-assesses her values and falls in love again with Isak, the simple, plain master of the wilderness now called Sellenra. Strangers, opportunists come and go; the seasons metaphorically embedded in the narrative (Struggle - spring; enjoyment of fruits of labour - summer; upset - autumn; and the dark night of the soul - winter) cycle about like spokes on the wheel of Hamsun's narrative. What remains after everything is the strength of the growth of the soil - the power of land and toil.

Hamsun's tone, his on-and-off use of the present tense, evokes oral storytelling, the primary art of the ancient (pre-classical) Greeks and Celts and the timeless conduit of fables and proverbs. As a tale of rustic folk and the homestead it is as close as the late art of the West comes to a prose Hesiod. The first translator of the book, W Worster, said that 'a more objective work of fiction it would be hard to find.' The matter-of-factness of Hamsun's narrator, his description of the characters' feelings couched in conversational speculations but never demeaning them, pointed to a different kind of fate for Western literature, one which is echoed in the flatness of his partial-contemporary Hemingway's prose, but which never gathered enough pace to attack the muggy but creative psychologism of Joyce, the synaesthesia of Dos Passos and the ornate factual-fictional reminiscences of Proust.

Growth of the Soil is anti-Impressionist and anti-Expressionist. It is the literary equivalent of Henri Rousseau, and therefore late in the unified theory of Western art, but timely nevertheless. With the bloodiest, most destructive war in history finished just over a year before the Nobel Committee's decision to award a novel so hostile to the idea of the city and its money and machines, it is no surprise that this point would have been considered insensitive if not pernicious to a wounded Europe's need to look to idyllic alternatives.

Hamsun's skepticism about the war and civilisation later led him to sympathise with Germany over England, with the tenets of Blood & Soil over the dogma of Capital. He refused to repent after the second war. His books remain in print and widely translated, such is the force of his vision.

Hamsun's Nobel acceptance speech:

http://www.nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/literature/laureates/1920/hamsun-speech.html

http://www.hamsun.dk/uk/